Gender and Climate Change in the MENA Region – Nexus or Opposition?

Even though the Conference of Parties (COP25) in December 2019 in Madrid was mostly a disappointment, a positive development was the agreement on a new 5-year Gender Action Plan (GAP). The GAP sets out gender-sensitive and intersectional aims and indicators to support women, indigenous groups, etc. This is a positive step to inclusive and just climate change policies in the future. So, how does gender relate to climate change globally and in particular in the MENA Region?

Climate change and gender are linked through an analytic lens – intersectionality – which is “a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects.” Intersectionality shows how power systems and privileges, as well as forms of discrimination, intersect in a world – highlighting power differences, as well as a call for taking responsibility and action by those in “powerful” societal settings.

Gender has a lot to do with who is causing/who caused climate change and who will bear the main impacts. Women from the MENA region, as well as men, will be impacted worse than their European counterparts and have fewer adaptation capabilities. Thus, to reinstitute intersectional justice, the industrialized countries that have and are still causing the majority of climate change, need to find ways to help the MENA region adjust financially and with their expertise.

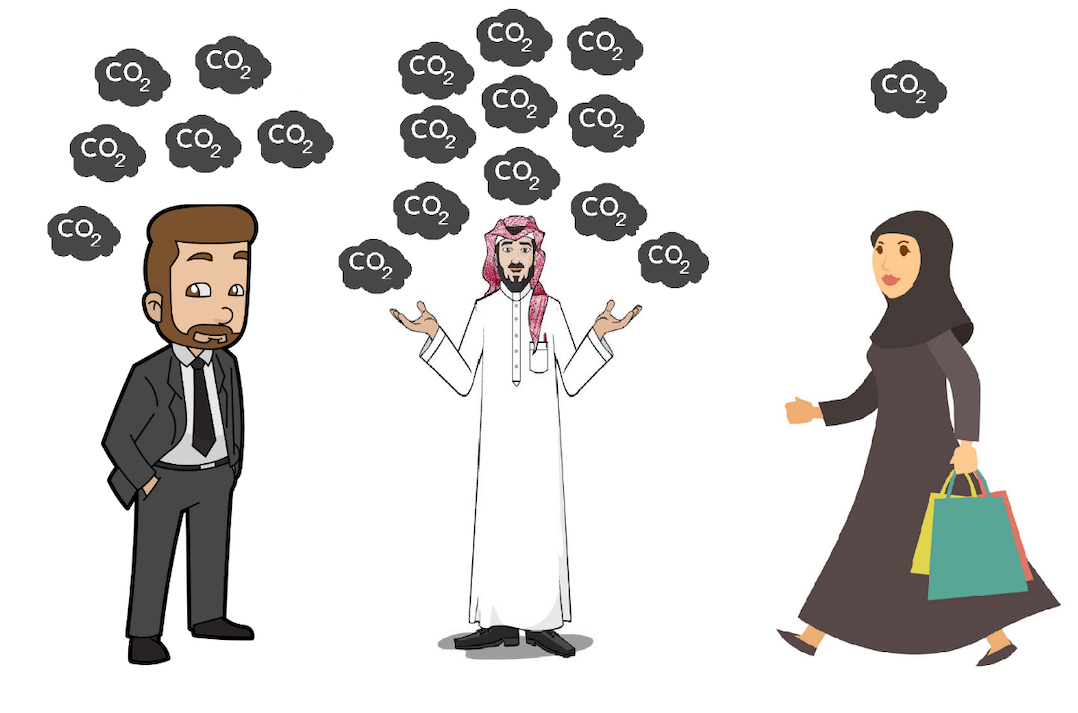

In order to underline the point, let’s do a sample calculation. Comparing a white, western European, middle-class man (from no onwards called Mr. Schmitz) with a low-income woman from a MENA country, (Ms. Amal), highlights that there are several systems of privilege and discrimination. The lifestyle of Mr. Schmitz includes extensive amounts of Co2 emissions compared to Ms. Amal, e.g. through the waste of food (e.g. 55 kg per year per person in Germany), as well as extensive consumerism. Mr. Schmitz belongs to the Upper-middle income to High Income in a world comparison - producing a majority of emissions, while also living in Europe where the average is 7,6 tCO2/Person.

In comparison, Ms. Amal, coming from e.g. Jordan, in 2014 Jordan had an average of 3,965 tCO2/Person per year. For low income, it is 1,6 tCO2/Person year. Nevertheless, as she is a woman, there are gendered differences in CO2 emissions – probably even less. Studies in Canada and the EU show that women produce fewer emissions on average (in Canada women only causing 25% of emissions, while in France men produce on average 21,67 % more emissions per capita per year).

Thus, Mr. Schmitz’s emission footprint is up to 6 times as high as Ms. Amal’s. If you would do this comparison and Mr. Schmitz would be from the United States, it would be eight times as high as Ms. Amal’s emission footprint.

Mr. Saud is a middle-class man from Saudi Arabia. For Saudi Arabia the carbon emission per person is 19,4 tCO2. Thus, average for the Upper Middle Income – is 12,9 tCO2. Saud emission footprint is more than 10 times as high as Ms Amal.

What are the implications for adaptation abilities?

Ms. Amal has less access to capital (social – e.g. facing racism, decreased mobility due to weaker passport - and physical – money, access to goods) and less access to mobility (due to ‘traditional gender roles’ e.g. as of care work, dependable persons, etc.) – she will struggle to adapt to climate change. And in comparison, between Western Europe and MENA – the MENA region will be hit by far harder by climate change, including desertification, worsening water shortages and decrease of resource access. This is in comparison to Mr. Schmitz, who will be impacted by climate change but due to his access to capital and mobility, he can adapt better, while also having fewer impacts in Europe.

According to a UNDP report on Asia Pacific, the following are the main factors for the gendered effects of climate change:

- “(G)ender-based differences in time use, access to assets and credit and treatment by markets and formal institutions (including the legal and regulatory framework) constrain women’s opportunities” – including limited land ownership (10- 20 % of lands are owned by women, while they do more than 50% of agricultural work)

- “Compared to men, women face huge challenges in accessing all levels of policy and decision-making processes”. Thus, women do not have just access to affect and create gender-sensitive policies “(S)ocio-cultural norms can limit women from acquiring the information and skills necessary to escape or avoid hazards (e.g. swimming and climbing trees to escape rising water levels)”

- “(A) lack of sex-disaggregated data in all sectors (e.g. livelihoods, disasters’ preparedness, protection of the environment, health and well-being) often leads to an underestimation of women’s roles and contributions”. Hence emergency response and preparedness are not adjusted to the needs of women.

What does this mean for the MENA region? We need to integrate gender analysis and mainstreaming into climate change mitigation and adaption plans to be able to prepare for the impacts of climate change. By incorporating minority groups such as women, youth, poor communities, etc. into consultation and planning, more effective and just policies and plans. Furthermore, it is crucial for the Global North and industrialized countries as well as the Gulf states to increase their support for those countries in the region most affected, but who had little part in creating climate change. By not only incorporating gender justice, but intersectional justice, we can.

###

Ronja Schiffer, FES Program Manager Regional Climate and Energy Project